The Joker’s Therapy Sessions

Author: Meena Al-Tikriti || Scientific Reviewer: Madison Wolf || Lay Reviewer: Nikita Sajeev || General Editor: Stephen Baak || Artist: Hailey Myers || Graduate Scientific Reviewer: Nikki Salla

Publication Date: May 22, 2021

In 2005, neuroscientist James Fallon sought to identify specific physiological markers of psychopathy. He did this by studying Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scans of the brains of psychopathic killers. While analyzing the images, Fallon noticed decreased activity within the frontal and temporal lobes - areas critical for compassion, morality, and self-control. This is an essential physiological marker of a psychopathological brain [1]. Fallon was simultaneously using images of his and his family's brains from an Alzheimer's study. To his surprise, he found the physiological marker in a scan of his very own brain.

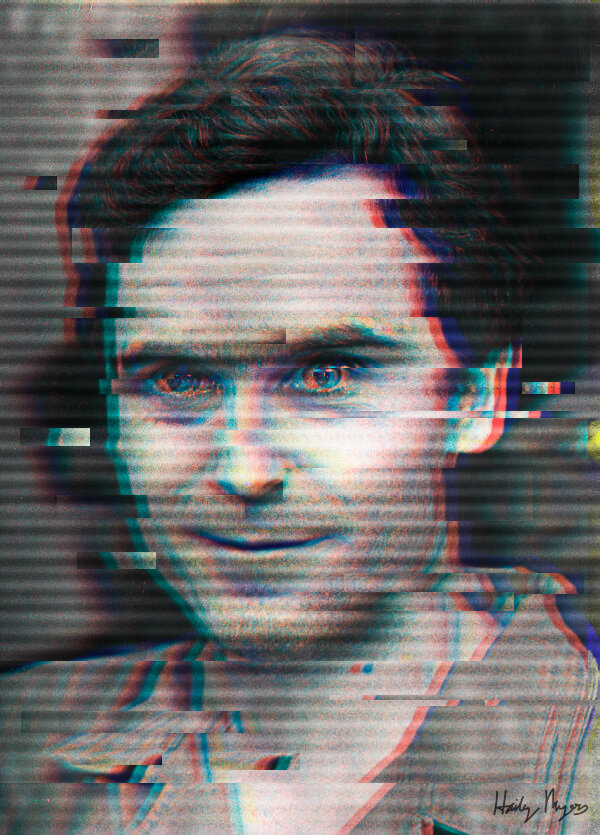

He had identified his neuronal activity as strikingly similar to notorious serial killers such as Ted Bundy and Jeffery Dahmer. Fallon lived an everyday life and struggled with minimal issues regarding his mental health. However, after exploring his family tree, he found a genetic linkage with Lizzie Borden, an American woman accused of brutally murdering her parents. He had no intention of commiting murder, rape, or acts of violence. Neurologically, him and Ted Bundy were identical, so what was the difference?

Despite the association between psychopaths & villainous characters, little is known by the general population about what a diagnosis of psychopathy entails. Surprisingly enough, psychopathy is statistically twice as common as anorexia, bipolar disorder, and paranoia and is just as common as obsessive-compulsive disorder, narcissism, and bulimia [1]. This means that, for disorders as common as psychopathy, the general public does not know nearly enough about these individuals. More importantly, the diagnosis of psychopathy is contingent upon a variety of factors, including and not limited to, anatomical markers and genetics.

What are the typical characteristics of a Psychopath?

Psychopathy, or antisocial personality disorder, as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), is a neurological personality disorder typically showing signs in early childhood [2]. Common traits include deficiencies in empathy, remorse, guilt, pathological lying, difficulties in romantic relationships, and irresponsibility [2]. Despite this, these individuals are also incredibly charming and charismatic, often using manipulation techniques to deceive others [2].

Psychopaths show an inability to recognize common emotions such as happiness, sadness, fear, anger, or shame, and a failure to sense threats or dangerous situations [1]. One of the most notorious examples of this was when researcher Essi Viding interviewed a serial killer and presented pictures of people making fearful facial expressions. The serial killer could not recognize the emotions, stating, “I don’t know what that expression is called, but I know it’s what people look like right before I stab them” [3].

Roughly 1% of the male, non-institutionalized population within the United States are estimated to be psychopaths [3]. Additionally, 93% of adult male psychopaths have had run-ins with the justice system, either in prison, jail, parole, or probation [3]. While female psychopaths do exist, they represent a small portion of the total psychopathic population. Much attention is given to male psychopaths, likely because males make up most of the prison population and are more likely to commit violent crimes [3]. However, psychopathy in males may be attributed to a specific X-linked gene encoding the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) enzyme.

The Biology behind Psychopathy:

It is currently understood that psychopaths express a low-activity variant of the MAOA gene called MAOA-L [1]. A significant amount of research has been aimed at deciphering the specific factors contributing to the development of psychopathy. While psychopathy-associated genes may be inherited from generation to generation, other factors impact whether a gene carries out its intended function via expression. Epigenetic changes - the modulation of gene expression by environmental or behavioral factors - can affect the manifestation of psychopathic traits. Essentially, the environment one lives in affects how a specific gene is expressed - or if it even is expressed at all. For example, the mere existence of the MAOA-L variant does not indicate psychopathic behavior [4]. The environment or one’s upbringing affects the expression of the gene, and therefore affects the outcome of one’s behavior. Events such as trauma or violence in childhood typically lead to the expression of MAOA-L, increasing the probability of a psychopathic phenotype [4] .

MAOA degrades neurotransmitters, chemical messengers that neurons use to send signals to each other. Neurons are separated by small gaps called synapses, and neurotransmitters typically diffuse from a presynaptic neuron (pre-gap) to a postsynaptic (post-gap) neuron, where they can bind to their respective receptors. However, after they are released, excess neurotransmitters need to be removed from the synapse for effective signaling thereafter. Monoamine oxidases play an essential role in this process, specifically in breaking down neurotransmitters called monoamines (a class of molecules including dopamine and serotonin) that are transferred back into the presynaptic neuron in a process known as reuptake. Mutations in the MAOA gene lead to reduced monoamine oxidase activity, causing monoamines to accumulate at the synapse. Variants of the MAOA-risk allele were studied in males and adolescents, and it was found that those who carried MAOA-L were more likely to exhibit traits associated with psychopaths [4].

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the amygdala are located within the paralimbic regions of the brain. These regions are responsible for morale, emotion, and behavior and abnormal activity have been linked with the expression of psychopathic traits [5]. For example, the amygdala regulates responses to emotional expressions; impairment there can lead to an abnormal response to a fearful face [5]. Additionally, impairment in the vmPFC can impair decision making, which may contribute to the lifestyle and predisposition that psychopaths have to drug abuse [5]. Many studies have found correlations between vmPFC and amygdala dysfunction, and further research may elucidate how pharmacological treatments can target these regions to benefit psychopathic individuals [5].

Can psychopathy be treated?

While many believe in post-criminal rehabilitation, psychopaths have proven to be challenging to treat. Treatment methods such as psychoanalysis, group therapy, client-centered therapy, psychodrama, psychosurgery, electroshock therapy, and drug therapy, have been relatively ineffective on psychopaths. During a treatment session, a psychotherapist wrote, “[psychopaths] have no desire to change, … have no concept of the future, resent all authorities (including therapists), view the patient role as … being in a position of inferiority, and deem therapy a joke and therapists as objects to be conned, threatened, seduced, or used” [2]. Often, individuals will use deception to avoid treatments like therapy or rehabilitation by displaying actions and behaviors they know are desired. These treatments, such as group therapy, may even help the psychopath manipulate and deceive others, as they use people's vulnerabilities and insecurities shared within group sessions against them [1]. In a well-known 1991 study that observed imprisoned psychopaths, participants who underwent treatment had a higher recidivism rate (the rate at which a convicted will reoffend) than those who did not [1].

However, some studies do seem to show promise regarding juvenile psychopaths. By resolving experimental & methodological flaws within past experiments, a comprehensive treatment seeking to revive these individuals' absent social connections was developed. Michael Caldwell and his peers from the University of Wisconsin created an intense treatment in which participants underwent several hours a day throughout six months. Caldwell and his colleagues aimed to revive the social connections within the juveniles by using methods like positive reinforcements for good behavior. After receiving this form of therapy, there was only 10% recidivism observed for those in the study, compared to the 70% recidivism observed in individuals within the control group who had received no therapy [1].

There may be hope for a modern-day psychopath. What is known for sure is that these individuals are not always the villains depicted on our TV screens. They live amongst us; they are our doctors, co-workers, and may even be our family members. What we do know is that a diagnosis of psychopathy is more complicated than just identifying one’s neural activity. We cannot identify them by placing them through an MRI or identifying the presence of a gene, explaining why James Fallon himself had no intent of committing violent crimes. Despite having the genetic makings of a psychopath, he lives a life of love rather than violence. If it were simply a matter of identifying anatomical features or genes, we would be much more effective at identifying psychopaths. Instead, it is a mixture of genetics and environment that curate people’s personalities, including that of a psychopath’s. Because of this, more research must be conducted to decipher these complicated factors to provide hope and a place in society for these individuals.

So, the next time you take an Am I a Psychopath Quiz from Buzzfeed, don’t take those results too seriously. Unless you pour your milk in before your cereal!

References

Kiehl, K. A., & Hoffman, M. B. (2011). THE CRIMINAL PSYCHOPATH: HISTORY, NEUROSCIENCE, TREATMENT, AND ECONOMICS. Jurimetrics, 51, 355–397.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Kiehl, K. A., & Hoffman, M. B. (2011). THE CRIMINAL PSYCHOPATH: HISTORY, NEUROSCIENCE, TREATMENT, AND ECONOMICS. Jurimetrics, 51, 355–397.

Williams, L. M., Gatt, J. M., Kuan, S. A., Dobson-Stone, C., Palmer, D. M., Paul, R. H., Song, L., Costa, P. T., Schofield, P. R., & Gordon, E. (2009). A polymorphism of the MAOA gene is associated with emotional brain markers and personality traits on an antisocial index. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(7), 1797–1809. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2009.1

Blair, R. (2008). The Amygdala and Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex: Functional Contributions and Dysfunction in Psychopathy. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 363(1503), 2557-2565. Retrieved April 14, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20208665