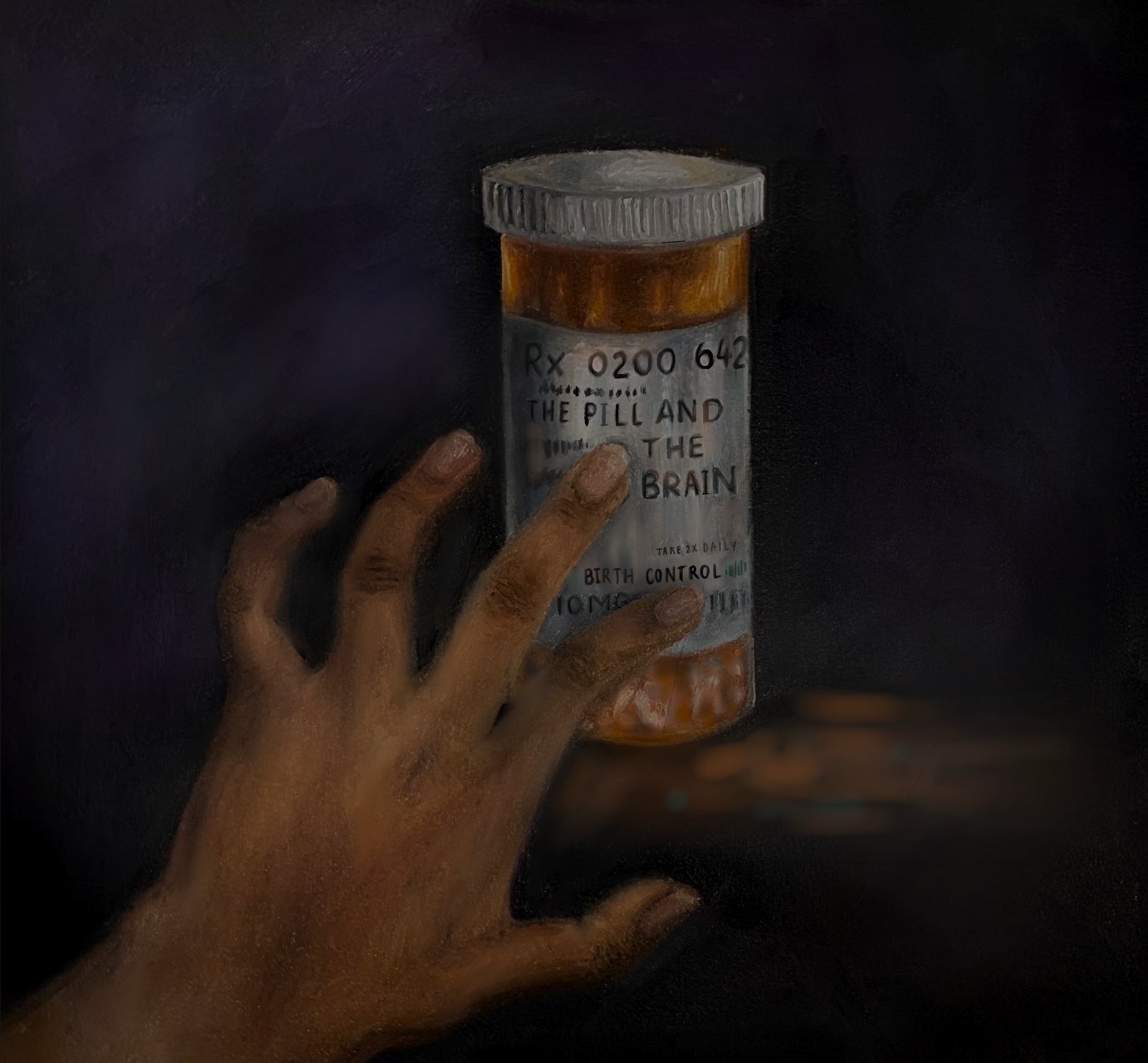

The Pill and The Brain: The Dismissal of Hormonal Birth Control’s Neurological Side Effects

Author: Daphne Wong || Scientific Reviewer: Ramneek Kaur || Lay Reviewer: Kaitlyn Lupole || General Editor: Yuliana Fartachuk

Artist: Esther Moola || Graduate Scientific Reviewer: Bryan McElroy

Publication Date: December 20th, 2022

When Sarah1 was a freshman in high school, she was excited to start taking the pill. In her consult with her doctor, they had discussed how starting hormonal birth control could make her periods easier to deal with. It felt empowering; less pain meant more time and energy for friends and school and soccer practices. But soon after starting, Sarah noticed big changes to the way she felt day-to-day; after only a few weeks, she cycled between feeling irritated and aggressive and feeling on the constant verge of tears.

At the same time a couple states away, fourteen year old Lia was on the same hormonal roller coaster. When her doctor prescribed her the pill, it felt very matter of fact. “It was like, ‘this is what everyone uses, so this is what you should use.’ It didn’t really feel like a discussion.” While her prescription was intended to balance hormones causing acne, she noticed weight gain followed by weight loss. Like Sarah, she began to notice changes in her mood, and a foggy haze of emotional numbness. How was one pill a day offsetting the crux of Sarah and Lia’s emotional world?

The word contraception refers to the intentional prevention of pregnancy by use of a device or behavior. The concept of preventing pregnancy is as old as the Old Testament, appearing in Aristotle's musings [1] and in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics [2]. Today, birth control is prescribed to many like Lia and Sarah every day; a century ago, this was not the case. In 1873, the rise of condoms as contraception in the mid-1800’s had come to a halt; Congress passed the Comstock Act, championed by Anthony Comstock, a religious fundamentalist [3]. The bill effectively banned doctors from legally providing patients with information about contraception of any form [4].

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America, widely known today as Planned Parenthood, formed in 1942, and began distributing information and contraceptives to American men and women [4]. The novelty of more control over one’s body was unforgettable; reproductive freedom had a new battlecry in the form of birth control. The first use of the phrase “birth control” was in a 1914 issue of Margaret Sanger’s The Woman Rebel newsletter [2]. Its utterance put a name to a much anticipated face: contraception in the form of oral medication.

The initial concept of contraceptive pills was to prevent ovulation, and in turn prevent conception. Pivotal experiments by Ludwig Haberladt in 1921 demonstrated that elevating levels of the hormone progesterone, which already exists in the human body, could be used to strategically halt ovulation. [5]

This concept of tricking the body into thinking a pregnancy is underway is the supporting skeleton of birth control research. Oral birth control today appears most commonly in one of three types: progestin (synthetic progesterone) only pills, combination pills that contain both progestin and synthetic estrogen (henceforth referred to as estradiol), and continuous use pills [6]. For those who take a continuous pill, the dose of hormone is the same in each daily pill; this form can be regulatory and alleviate symptoms of chronic illnesses that cause painful, irregular cycles, or treat acne and hormonal deregulation (like in Lia’s case) [7].

In pop culture, hormones are often the culprit to blame for angsty attitudes of teenagers, weepy pregnant women, and hypermasculine behavior. But how do they actually work? Within the human body, hormones send important messages to cells about how to develop and change. The endocrine system, which regulates hormone production and movement, reaches widely throughout the body; some of its checkpoints reside in the brain, the thyroid, and even the kidneys [8].

After production, hormones travel through the body’s highway- the bloodstream - to their destination. While hormones serve similar purposes, they each have individual unique shapes, and receptors that relay their respective messages [9]. In simpler terms, hormones are not too different from package delivery in the mail: a specific good is wrapped up and addressed, transported to an address, and hopefully ends up in the intended hands.

Understanding the behavior of natural hormones was only the first step in developing “the pill”; mass production and prescription was going to require synthetic hormones. Stanford chemistry professor Carl Djerassi struck contraceptive gold in 1951; he discovered a way to synthesize norethindrone, a type of progestin that sends the same signals to the body as progesterone [10].

But these fresh faces, progestin and estradiol, were not carbon copies of estrogen and progesterone that already exist within the body. While they successfully reach the right receptors and block ovulation, they also interact with other receptors. These unintended reactions can produce a range of side effects, and create a chemical domino effect within the body [11].

Testosterone, the sex hormone most known for its masculinizing effects in males, belongs to a separate class of hormones called androgens. Androgens bind specifically to androgen receptors [12]. However, progestin can also interact with these androgenic receptors. Like a very social party guest, progestin can unintentionally mimic testosterone’s impact on the body as well [13]. This can be especially problematic for transgender men and individuals assigned female at birth as they take birth control as well as cross hormone therapy regimens [14]. For patients taking birth control and doctors prescribing it, this space is nebulous; hormones may be completing their assigned tasks, but at what cost?

Studies in the last two decades suggest that these androgenic interactions actually lead to physical changes in parts of the brain. In 2010, Austrian researcher Belinda Pletzer compared brain scans of individuals on birth control with those not on birth control. She found that those on birth control had growth in their prefrontal areas (behind the forehead, associated with self control and emotion), as well as in the hippocampus (key for integrating memory) [11].

On the surface, this sounds like a win-win: effective contraception, opportunity for treating other conditions, and brain growth. However, from firsthand accounts from patients, hormonal birth control’s impact seems to span much further than an additional few millimeters on a brain scan. What causes mood swings experienced by individuals like Sarah and Lia, who started the pill for the expected benefits?

In 2021, New York researchers at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine took a closer look into how exactly hormonal birth control impacts brain structures and function. Two brain regions heavily involved in these processes are the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus. The pituitary gland serves as the host of many hormone receptors discussed above.

The hypothalamus, located right above the pituitary gland, regulates a myriad of functions from heartbeat to movements. However, its main goal is to maintain homeostasis or balance in the body. [11] If the body was a public transit system, the hypothalamus is the busy transfer stop with interchange to different subway lines. The endocrine system (containing hormone release and regulation) and nervous system lines intersect here. The hypothalamus also translates emotional signals from the brain cortex into physical feelings. Before a big presentation or interview, your hypothalamus is the culprit for the butterflies in your stomach and increased heart rate [15].

It is no surprise that introducing new artificial hormones offsets these regulatory structures, and sometimes disrupts emotional equilibrium. A typical combination pill prescription might list up to eighteen common side effects, including nausea, headaches, weight loss and gain, and changes to menstrual cycle [16].

Psychological symptoms can cause a loss of objectivity; it is easy to forget what “normal” is supposed to feel like. When describing her mood swings, Lia iterated how difficult it was as a young teenager to differentiate between normal changes in mood, and something more serious. Lia’s experience is backed up by data; a 2019 study found a correlation between the prescription of two types of birth control progestins with diagnoses of depression [9]

The burden of neurological side effects is only amplified by the frustration of not knowing exactly what is happening in one’s body. Lindsay, a college junior, started the pill as a form of contraception. The side effects she experienced were difficult to manage; the changes to her body fueled insecurity. There was a disconnect between who she felt she was, and how she looked physically and felt emotionally. Closing that gap felt out of her control.

Listed at the bottom of most birth control information pamphlets is a recurring phrase: if you experience any side effects, contact your doctor for medical advice. However, how are these calls for relief answered? A 2018 study found that when it comes to pain in general, adolescent women in particular are more likely to experience dismissal from doctors than their male peers. Dismissing reactions ranged from minimizing the patient’s experience, claiming the symptoms were psychosomatic, or in some cases, suggesting the patients were faking their pain. [17]

Weakened lines of communication between a patient and their doctor often originate at their initial consult. In one study that evaluated consults in which doctors prescribe birth control, Dr. Krystale Littlejohn observed just over one hundred consults where doctors discussed birth control with their patients in different health clinics around San Francisco. She found that in about a quarter of the visits, no specific side effects were mentioned at all. In over half of the appointments in which side effects were discussed, they were painted as something unlikely to occur whereas the possible pros of being on birth control (lighter periods, a more regular cycle) were often depicted as guarantees [18].

Experiencing a benefit-heavy consult was the case for Ingrid, a college student who started birth control her freshman year. Her takeaway was that side effects were possible, but moreso “something to skim, then tear off and throw away”. However, irregular bleeding which she tried to brush off as something small and manageable snowballed, becoming physically taxing and emotionally exhausting. Experiencing side effects was not new to her; she had to weigh the pros and cons of side effects when she had started anxiety medication years before: “But I wish that didn’t have to be the case. You’re basically deciding whether or not you want to feel worse in one way or another.”

Unfortunately for those experiencing side effects and those trying to treat them, there is no one-size-fits all answer. Even without the miraculous invention of side-effect free birth control tomorrow, there is plenty of room for improvement in patient-doctor communication. Just the tone of words exchanged in consults themselves could also have a big impact. When Sarah was experiencing extreme mood swings for the first time, she was told to “wait it out”. A step in the right direction could have been hearing someone else’s voice acknowledging how she felt, and how fiercely it was impacting the reality of her everyday life.

When side effects like irregular periods outweighed the benefits of birth control, Ingrid decided to go off the pill. When asked what might have facilitated the process, she expressed, “I wish someone had just explained to me why this was happening to my body.”

Lia, who experienced mood swings coupled with weight fluctuation, expressed that if she had known what to look for, she might have spotted her changes in mood earlier, and taken them more seriously. When she changed her birth control after two years, she describes the sensation of a fog lifting, and she wished the relief could have come a lot sooner.

What Ingrid, Sarah, and Lia sought out of their follow up consults was more than just a solution– it was validation. The term “side effect” suggests a level of secondary-ness. In reality, these unintended symptoms can become the most central experienced outcome for many patients. Two truths can coexist: neurological side effects can be predictable and somewhat “normal”, while also being deeply detrimental. While the investment in more revolutionary drugs and continued studies are crucial, there’s changes to make outside of the lab, in everyday doctor’s visits, face to face.

Despite the multifaceted nature of its pros and cons, birth control’s original intended purpose plays a pivotal and irreplaceable role in our society. When Roe v. Wade was repealed in June of 2022, google searches of “IUD”, “birth control”, and other methods surged in the days that followed [19]. Current research on birth control has mostly centered around creating a wider variety of hormone combinations and tweaking their delivery systems, as opposed to adventurous overhauls. This stagnancy is rooted in a lack of federal funding for birth control research particularly in adolescents, despite the fact that they make up most of oral birth control’s target demographic [20].

Meanwhile, promising strides are being made in a gel form of male birth control. The gel contains a hormone called Nesterone which works to decrease sperm production, and synthetic testosterone to offset Nesterone’s unintended impact on libido [14]. The study’s success suggests the foreseeable future of birth control may be less about achieving perfection, and more about a shift towards equity.

The way “the pill” functions within the body and within our society is intricate; solutions to its weaknesses will not be as simple as waiting it out. Dismal research funding, dismissive care, and minimizing women’s pain all stem from the same place: a culture that does not see uncomfortable women as an urgent problem to solve. Perhaps that is the most difficult pill for all of us to swallow.

Footnotes:

All names of interviewed students have been changed for privacy.

References:

Definition of Contraception. (n.d.). www.merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved November 23, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/contraception.

A Timeline of Contraception | American Experience | PBS. (n.d.). Www.pbs.org. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-timeline/

Encyclopædia Britannica. (n.d.). Comstock Act. Britannica Academic. https://academic-eb-com.libproxy.temple.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Comstock-Act/124952

Gordon, L. (2002). The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America. University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9033-7.

Chen, K. X. (2021, April 21). Oral contraceptive use is associated with smaller hypothalamic and pituitary gland volumes in healthy women: A structural MRI study. NCBI. Retrieved November 23, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8059834/

Cooper, D. B., & Mahdy, H. (2020). Oral Contraceptive Pills. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430882/

Fraser, I., & Weisberg, E. (2015). Contraception and endometriosis: challenges, efficacy, and therapeutic importance. Open Access Journal of Contraception, 105. https://doi.org/10.2147/oajc.s56400

Hormones: What They Are, Function, Types. (2023, February 23). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22464-hormones.

Ditch, S., Roberts, T. A., & Hansen, S. (2020). The influence of Health Care Utilization on the association between hormonal contraception initiation and subsequent depression diagnosis and antidepressant use. Contraception, 101(4), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2019.12.011.

Dalton, L. (2001, September 4). Carl Djerassi Reflects on the Pill as It Nears Its 50th Birthday. Stanford News Service. https://news.stanford.edu/pr/01/thismanspill295.html.

Pletzer, B. A., & Kerschbaum, H. H. (2014, August 21). 50 Years of Hormonal Contraception-Time to Find Out What It Does to Our Brain. Frontiers in neuroscience. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4139599/.

McEwan, I. J., & Brinkmann, A. O. (2000). Androgen Physiology: Receptor and Metabolic Disorders. PubMed; MDText.com, Inc. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279028/#:~:text=The%20androgen%20receptor%20(AR)%20binds

Some Men Use Hormonal Birth Control — Here’s How. (2020, April 29). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/what-happens-if-a-guy-takes-birth-control

Spotlight: One year and counting: Male birth control study reaches milestone. (n.d.). https://www.nichd.nih.gov/. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/newsroom/news/080222-NEST

Ackerman, S. (1993). Discovering the brain. National Academy Press.

Cunha, J. P. (2022, May 31). Side Effects of Aviane . Aviane Side Effects Center. https://www.rxlist.com/aviane-side-effects-drug-center.htm.

Igler, E. C., Defenderfer, E. K., Lang, A. C., Bauer, K., Uihlein, J., & Davies, W. H. (2017, December). Gender Differences in the Experience of Pain Dismissal in Adolescence . Journal of Child Health Care. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29110522/

Littlejohn, K. E., & Kimport, K. (2017, October 16). Contesting and Differentially Constructing Uncertainty: Negotiations of Contraceptive Use in the Clinical Encounter. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6101241/.

Datta, P. K., Chowdhury, S. R., Aravindan, A., Nath, S., & Sen, P. (2022). Looking for a Silver Lining to the Dark Cloud: A Google Trends Analysis of Contraceptive Interest in the United States Post Roe vs. Wade Verdict. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27012

Capozzi, L. (2019, January 23). How a Lack of Federal Funding for Teen Contraceptive Research Hurts Us All. Policylab.chop.edu. https://policylab.chop.edu/blog/how-lack-federal-funding-teen-contraceptive-research-hurts-us-all