The Brain and Language Development: Exploring the Role of Nature vs. Nurture

Author: William Miller || Scientific Reviewer: Anushka Gangupanthulu || Lay Reviewer: Kendall Pickney || General Editor: Shruthi Kundoor

Artist: Sara Fuertes || Graduate Scientific Reviewer: Lily Steele

Publication Date: June 11th, 2025

Introduction

Why is calculus not taught to infants at birth? At first, this may seem like a ridiculous question with an obvious answer: children’s brains are not as developed and lack the cognitive ability required to perform calculus. This assumption also applies to many other advanced fields like physics and complex literature, with the consensus that adolescents and early adults are much better learners than children. However, language acquisition is a striking exception.

Most people naturally learn their first language from birth, while learning their first language as an adult is rare. The difference in language acquisition between children and adults is more evident in second-language acquisition: people who learn two languages from birth–known as simultaneous bilinguals–show advantages including native-like accents, better grammar, and greater language processing ability compared to those who acquire a second language later in childhood or adulthood [1,2]. This raises a major question: Why are young children more efficient language learners than adults? This article will explore the nature versus nurture debate of language acquisition by studying two major theories of language acquisition– B.F. Skinner and Noam Chomsky’s theories of language acquisition–followed by an investigation of the critical period of language learning and the role of neuroplasticity. Finally, an analysis of the case study of Genie, a girl deprived of language during her early childhood, will be used to support these theories and concepts.

Nurture: B.F. Skinner’s Behaviorist Theory

Skinner, the “Father of Behaviorism,” proposed that behaviors are learned, or as he put it, “conditioned,” through experience and reinforcement rather than through an innate ability [3]. The basis of behaviorism is operant conditioning, which explains that rewards or punishments shape behavior. Positive behaviors can be reinforced by receiving something good, like praise, or removing something bad, like a teacher taking away homework. Conversely, punishment discourages negative behavior, whether through receiving something bad, like physical punishment, or removing something good, like getting your phone taken away [3]. According to Skinner’s behaviorist theory of language acquisition, like all other behaviors, is learned through operant conditioning [3].

Children learn language by mimicking what they hear in their environment and through the subsequent reinforcement that comes with correct usage. For example, if a child says “milk” and their mother immediately rewards them with milk, they will associate the word “milk” with its meaning, which enhances their knowledge of the language [4]. Overall, Skinner suggests that children’s language development revolves around imitation and reinforcement, and it depends on their environment, including how they are nurtured.

Nature: Noam Chomsky’s Nativist Theory

Although Skinner’s theory is useful, it assumes that language acquisition should be equally efficient at all ages, which is not the case. Conversely, Chomsky developed his language acquisition theory to directly critique Skinner’s behaviorist theory [5]. He believed that even though children have limited exposure to language input, they rapidly develop and master their first language. Chomsky argued that language development could not be explained through imitation, reward, and punishment, but was due to innate ability and cognitive structures. His nativist theory of language acquisition proposed that children have the innate ability to learn language and grammar rules. This would explain why adults are less efficient language learners than children: their innate ability to acquire language declines over time due to neurological changes as people age.

Two key aspects of Chomsky’s nativist theory are the language acquisition device (LAD) and universal grammar [4]. Chomsky hypothesized that humans are born with a brain structure, known as the LAD, that allows us to learn and acquire languages [6]. Universal grammar, on the other hand, is the idea that all languages are made up of similar grammatical rules, which humans innately understand [4]. In other words, the LAD is the cognitive mechanism for understanding language, while universal grammar is the linguistic and grammatical knowledge within the LAD [6]. However, the LAD is hypothetical, and there is no neurological evidence of a language acquisition device in the brain. Unlike Skinner’s theory, Chomsky’s nativist theory explains that children are more effective language learners than adults because of biological factors, or nature.

What is the Critical Period and How Does it Work?

Chomsky’s work suggests the existence of a critical period for language acquisition. While there are critical periods for many behaviors, the critical period for language acquisition is specifically defined as a developmental period from birth to puberty, during which a child can fully acquire and use a first language and potentially another [7]. Suppose a person does not receive adequate exposure to language within this period, such as hearing the language being used or practicing the language. In that case, they may struggle significantly or be unable to acquire language-related abilities later in life [8].

The age of first exposure to language is one of the most important factors in language acquisition [2]. Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard, and Boston College administered an interactive grammar test to assess proficiency in the English language. Participants who indicated they did not speak English from birth were asked the age at which they were first exposed to English. The researchers compared English proficiency to the age of first exposure. They found that English language learners who had their first exposure before age 12 were able to achieve a native-like proficiency, with increasing age of first exposure relating to a minimal decrease in proficiency [2]. After 12 years old, the decrease in proficiency with age was more dramatic, with a particularly steep drop around 17-18 years old [2]. Their research highlights the existence of a critical period for language development that ends between the ages of 10 and 12.

Although there is sufficient evidence of a critical period for language acquisition, how exactly does it work on the neurological level? The neurological mechanisms of a critical period for language in humans are not yet fully understood. Much of our current understanding of critical periods comes from animal studies, particularly vision, in both animals and humans [9]. If an animal’s eye is occluded (has a blockage of vision) after birth during the critical period, neuroplasticity- the malleability of neuronal connections in response to lived experiences [8]- may increase the cortical representation of the unoccluded eye and decrease that of the occluded eye. This will cause the occluded eye to remain blind even if the occlusion is removed [9]. However, this neuroplasticity will not occur if the occlusion occurs after the critical period, and vision will not be impaired once the occlusion is removed [9]. This phenomenon extends to humans: If a baby is born with a cataract or a clouded eye lens, then they will remain blind even after the cataract is removed. Conversely, a person who develops a cataract as an adult typically has their vision restored after its removal, most likely due to the lack of neuroplasticity [9].

Some researchers believe that language acquisition follows a similar process, although there is no consensus among researchers [2]. The current debate for children’s superior language ability is whether it comes from increased neuroplasticity during childhood or from the additional years of learning or practicing a language that comes with learning it early [2], yet another example of nature vs nurture. However, if future research provides definitive proof of a critical period for language acquisition and a consensus is reached, neuroplasticity can explain why children are more effective language learners than adults on a neurological basis.

Neuroplasticity is especially important during early childhood, with the malleability of neuronal connections in the brain’s structure and within neural circuits being able to facilitate learning, memory, and other cognitive functions [8,9]. As a person ages and surpasses the critical period, these neural connections become less flexible, meaning that large changes to the brain become more difficult, such as language acquisition [8]. Neurologically, critical periods are thought to be characterized by high levels of neural plasticity and the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [8]. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that makes a neuron less likely to fire [8]. Early within the critical period, sensory experiences have a greater impact on our brains, and an increase in GABA uptake reflects this. Thus, linguistic input would have a greater effect on the developing brain. However, as we grow older and the critical period ends, our brain matures and is less affected by sensory experiences. Thus, GABA uptake decreases [8], and our brains would have more difficulty processing linguistic input. Overall, the critical period theory is viable, not only because of the research evidence supporting it, but also because it can be explained both neurologically and theoretically.

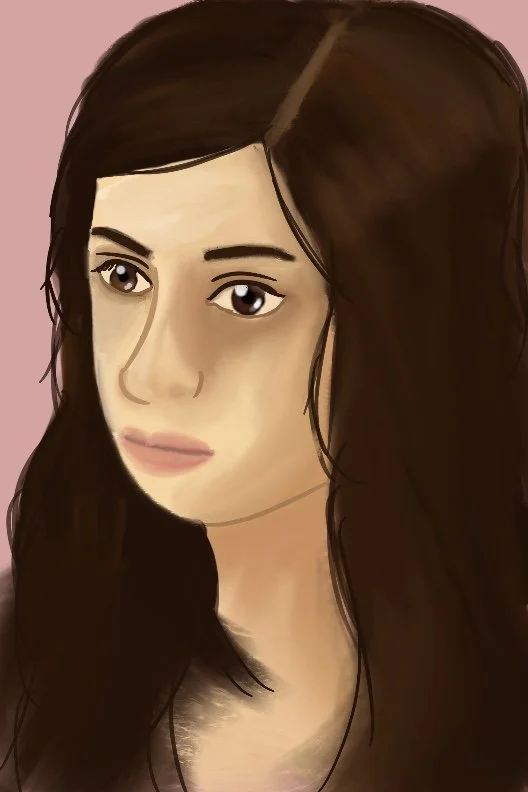

The Case Study of Genie Wiley

Due to ethical concerns, testing the viability of language acquisition theories is difficult for scientists, especially the critical period hypothesis. Instead, scientists must study children who have experienced prolonged isolation during childhood. One notable case study is Genie Wiley, who grew up in isolation until she was about 14 years old. Although Genie was born healthy, she was diagnosed with congenital hip dislocation, and her father also believed that Genie had mental disabilities [10]. As a result, from about 20 months to almost 14 years old, her father isolated her from the world, until she was discovered by authorities [11]. During the day, he confined her to a toilet seat, and at night, he kept her in a crib, hurting her if she made a sound. Her mom was also forbidden from taking care of Genie, so no one formally spoke to Genie during this time. Almost immediately after being discovered, scientists began studying Genie since she was found after the supposed critical period [11]. During this time, her linguistic development was much slower than that of typical children, but her progress indicated that some degree of first language acquisition could occur after the critical period [11]. However, this could be explained by the psychological trauma that she endured from her father, which hindered her socialization. At 18, Genie moved in with her mother, who sued the researchers for exploiting and overworking her daughter, causing this research to stop [10]. Now in her 60s, Genie’s language progression has significantly slowed since her teenage years [10].

Conclusion

Overall, Genie’s case study challenges Skinner’s behaviorist theory as she was able to imitate some words said by the researchers, but she did not fully develop language. In contrast, Chomsky’s nativist theory seems better supported, although the concepts of language acquisition device and universal grammar are purely theoretical. Genie’s case most significantly supports the critical period hypothesis because her ability to acquire a first language was decreased after surpassing the critical period, and language acquisition became even more difficult after her mother ended the research. The bizarre nature of Genie’s story ultimately raises more questions than answers, yet it provides sufficient evidence to support the critical period hypothesis. Despite many researchers’ attempts to teach Genie language after she surpassed the critical period, she showed only limited progress. Her case proves that language learning is unfortunately constrained to a critical period during early development. Our brains, just like Genie’s, are naturally equipped to learn grammar and language to the fullest extent. However, Genie’s story proved that although we all have an innate or natural ability to learn language, without proper care, environmental linguistic input, or being properly nurtured, specifically within the critical period, language can never fully develop. In the end, nature and nurture are both necessary for language development.

References

Delcenserie, A.., & Genesee, F.(2017, October). The effects of age of acquisition on verbal memory in bilinguals. Sage Journals, 21(5), 521–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916639158

Hartshorne, J. K., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Pinker, S. (2018, August). A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers, Cognition, 177, 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.007

Birenbaum, B. (n.d.). B. F. Skinner: Theory & experiments, The Berkeley Well-Being Institute. https://www.berkeleywellbeing.com/b-f-skinner.html

Lemetyinen, H. (2023, September 7). Language Acquisition Theory. Simply Psychology.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/language.htmlChomsky, (1959). A review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal behavior. Language, 35, 26

Language Acquisition Device. (n.d.) Psychology. https://psychology.iresearchnet.com/developmental-psychology/language-development/language-acquisition-device/

Yule, G. (2022). Second language acquisition. In, The Study of Language (8th ed., pp. 228-236). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009233446

Nickerson, C. (2024, January 24). Critical period in brain development and childhood learning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/critical-period.html

Power, J. D., & Schlaggar, B. L. (2017, January/February). Neural plasticity across the lifespan. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology, 6(1), e216. https://doi.org/10.1002/wdev.216

Genie - The Feral Child. (2023, September 13). Practical Psychology. From,

https://practicalpie.com/genie-the-feral-child/Fromkin, V., Krashen, S., Curtiss, S., Rigler, D., & Rigler, M. (1974). The development of language in genie: A case of language acquisition beyond the “Critical Period.”

Brain and Language, 1(1), 81–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934x(74)90027-3