Neuroscience Behind Anxiety: Cognitive Effects Across Anxiety Disorders

Author: Aleena Nasir || Scientific Reviewer: Esmeralda Lua || Lay Reviewer: Ola Szmacinski || General Editor: Erin Kathlyn Michel || Artist: Molly Barron || Graduate Scientific Reviewer: Matt Mattoni

Publication Date: December 20, 2021

It’s normal to feel anxious about everyday stressors, like the first day of school, getting a tattoo, or finances. But at a certain point, anxiety can become much more than just a worrisome feeling. Clinical anxiety is an apprehensive expectation or an excessive worry that remains constant and is difficult to control [1]. The distinction between anxiety and clinical anxiety is important to point out. To say you have clinical anxiety, diagnosed as an anxiety disorder, is to say that anxiety causes significant distress or impairment in daily functioning [2]. It is important to note that mental illness carries a stigma in our society. Because of this, there are common misconceptions surrounding mental illnesses, namely anxiety. Clinical anxiety is as real as any physical illness—it should be treated with the same compassion.

A major consequence of anxiety is that it can impair cognition, otherwise known as “information processing” in the brain [3]. Specific areas of cognition affected by clinical anxiety may include attention/control, memory, executive functioning, sensory-perceptual processing, etc. [3]. The highlight of this analysis will be the effects of clinical anxiety on attention specifically. By examining the relationship between clinical anxiety and cognition, we are able to address a common symptom of anxiety. With the help of applicable scientific findings, the goal of this article is to unpack the altered cognitive performance brought on by clinical anxiety.

Establishing how clinical anxiety manifests is the first piece of the puzzle in understanding how cognitive performance is affected by clinical anxiety. Feeling anxious is commonly associated with some sort of fear [3]. However, fear is the initial feeling from an existing threat while anxiety is a more persistent worry accompanied with symptoms of physiological arousal [1]. Anxiety manifests by threat detection beginning in the amygdala, which has key functions in the processing of emotional stimuli such as fear [3]. Next, the amygdala sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus which is responsible for regulating things like body temperature, emotions, blood pressure, and heart rate. Once the hypothalamus receives this signal, it activates two systems: the sympathetic nervous system and adrenal-cortical system. Specifically, the pituitary gland first produces a hormone [4]. This prompts the adrenal gland which increases the production of cortisol, your body’s main stress hormone [4]. The activation of these systems causes muscle tension, increased heart and breathing rates, and high blood pressure. This is how our body responds to stress; it is commonly known as the “fight or flight” response. When experiencing anxiety, our fight or flight system is working in overdrive. This means that your sympathetic nervous system is overactive or dysfunctional. In other words, those who suffer from clinical anxiety do not simply react differently to stress or fears; there are neurological differences in how their brain works [5].

To further explain these neurological differences, we must understand how attention works in the brain. The attentional control theory (ACT) states that anxiety impairs cognitive performance by increasing cognitive interference or the bottom-up, stimulus-driven processing of threatening information [6]. Simply, bottom-up, stimulus driven processing refers to sensory analysis that begins with what our senses detect [6]. Essentially, in bottom-up processing you are inputting raw sensory information from the external environment to build a perception. To further explain, let's say an individual with a form of clinical anxiety is driving a car. This individual is analyzing the environment; cars and trucks passing by, stop lights, bikers, and pedestrians. This is the raw sensory information referred to as the “stimulus”. Once they capture the stimulus, their eyes transmit this information to the brain. Until finally, their perception of driving on the road is formed. This individual, however, will have a skewed perception. They will focus on the possible dangers that could arise from the stimulus. In this context, someone with a form of clinical anxiety will be thinking of the possibilities of something bad happening on the drive.

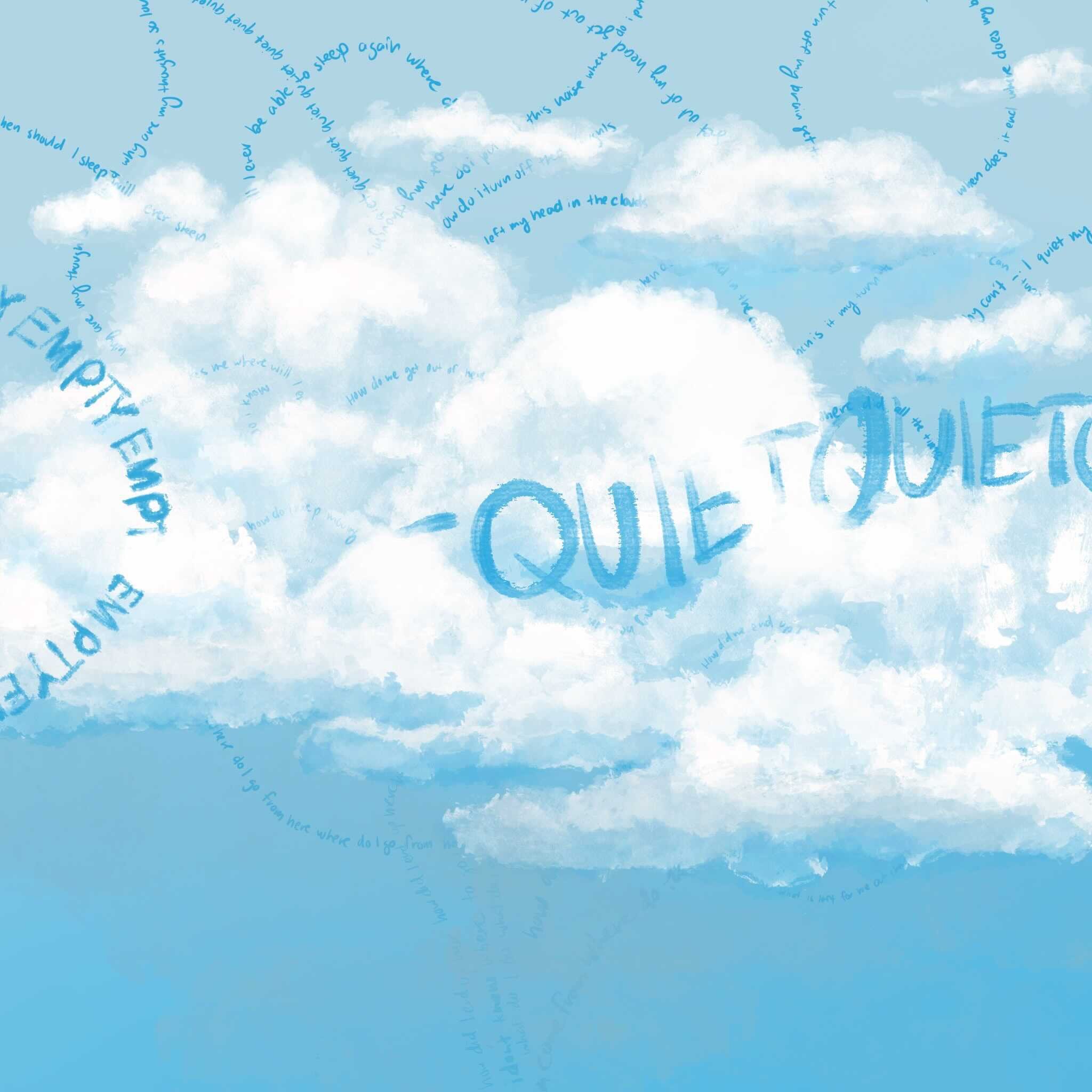

The cognitive interference theory states that clinical anxiety impairs cognitive performance by increasing cognitive interference [6]. Cognitive interference is when a cognitive function becomes consumed by a threat. For example, people with clinical anxiety tend to scan their external environment for threat cues, meaning they allocate their attention to threatening information [6]. Threat cues are the possible dangers that may or may not occur from the threat. For example, a student with clinical anxiety attends a fraternity party. Whereas the average student would enter the party and mingle, the anxious student assesses their surroundings. The student eyes open drinks, a set of stairs, and a pool. The student immediately attends to thoughts like the possibility of someone slipping Rohypnol in their drink, falling down the steps, or drowning in the pool; these are considered threat cues. These threat cues then capture their attention and are unable to disengage from the threat. Ultimately, the inability to disengage from the threat prevents an individual from taking part in other cognitive processes [6]. This cycle promotes increased attentional bias towards negative stimuli [7]. In this instance, the cognitive function consumed by the threat is attention.

In layman's terms, people with clinical anxiety have difficulty attending to any other thoughts when fixated on threat cues. There is evidence for attentional bias toward negative stimuli in anxiety disorders, dispositional anxiety, and state anxiety [3]. If attention is compromised like so, then people with clinical anxiety can suffer from long-term “debilitating intrusive thoughts and feelings as well as dysregulated attention processes” [3]. Undoubtedly, difficult to disengage from negative stimuli interferes with information-processing [8]. Research suggests that this difficulty likely contributes to the development and maintenance of clinical anxiety while also amplifying the major symptom; chronic, pathological worry [6].

With the support from applicable scientific findings, we explain how anxiety manifests and impairs cognition, specifically in the domain of attention. As explained above, people with clinical anxiety have neurological differences in how their brain processes information. These differences impede cognitive processing by developing attentional biases. The role of attention processes and its perpetuation on clinical anxiety is supported by reductions in anxious symptoms, followed by improved attentional control and decreased biases [8]. The impact of anxiety on cognition is complex, as all the functions of the brain are not fully discovered or explained. Anxiety can be present in various forms and symptoms since all individuals are entirely unique. Because of this, it is vital for us to recognize these neurological ramifications of clinical anxiety so that we encourage researchers to better address the neurological implications of clinical anxiety. Ultimately, this could aid in facilitating better treatments for clinical anxiety.

References:

Hoge, E. A., Ivkovic, A., & Fricchione, G. L. (2012). Generalized anxiety disorder: diagnosis and treatment. Bmj, 345.

Dobmeyer, A. C. (2018). Anxiety. In Psychological Treatment of Medical Patients in Integrated Primary Care (pp. 71–86). American Psychological Association.

Oliver Joe Robinson, Katherine eVytal, Brian R Cornwell, & Christian eGrillon. (May 01, 2013). The impact of anxiety upon cognition: Perspectives from human threat of shock studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7.

Smith, S. M., & Vale, W. W. (2006). The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 8(4), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.4/ssmith

Kim M. Justin, Brown Annemarie C., Mattek Alison M., Chavez Samantha J., Taylor James M., Palmer Amy L., Wu Yu-Chien, Whalen Paul J. (2016). The inverse relationship between the microstructural variability of amygdala prefrontal pathways and trait anxiety is moderated by sex. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 10, 93. 10.3389/fnsys.2016.00093

Angelidis, A., Solis, E., Lautenbach, F., Van, . D. W., Putman, P., & Kavushansky, A. ( 2019). I’m going to fail! Acute cognitive performance anxiety increases threat-interference and impairs WM performance. Plos One, 14, 2.)

Schoorl, M., Putman, P., & Van Der Does, W. (2013). Attentional bias modification in posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 82(2), 99-105.

Blackmore, M. A. (2011). Attentional bias for affective stimuli: Evaluation of disengagement in persons with and without self-reported generalized anxiety disorder. Temple University.